When minibeasts beat Minecraft

Lessons from a year of bringing biodiversity to kids' doorsteps

Dear friends,

Before we get started on this week’s post proper, I am announcing that I have changed my offer for paid subscribers! Paid subscribers now get access to my Research Deep Dives series. These are exclusive posts on the first Tuesday of every month, providing a deep dive into a research paper on nature connection, or on the health and wellbeing benefits of biodiversity. If you want the fine detail behind the research, upgrade to paid today.

Your usual Friday post begins here…!

I don’t know how you spent your 2019, but I spent most of mine masquerading as a one-woman touring production company.

Over spring and summer, I travelled around the UK visiting primary schools and delivering biodiversity workshops. I arrived in an old car with the back bumper gaffer taped on, packed full of kid-friendly field kit—collecting pots, magnifying glasses, sweep nets, beating trays, ID guides and lots of insect stickers.

Ostensibly, the point was to explain the basics of ecology, what biodiversity is, why it matters and how we might go about measuring it. This framing is what got the teachers to say ‘yes’ and let me in.

But my own personal goal (not that I didn’t follow through on the above, of course) was to take the children outside and let them run wild with the ecology kit. I wanted them to enjoy looking for insects and minibeasts in places they wouldn’t otherwise have been encouraged to look—in short, to come away with the idea that ecology, learning outside and little creatures so often feared are important and enjoyable.

In the end, I wound up delivering these sessions to over 400 children, aged between seven and 11, in the space of three months. Each session only lasted about an hour, but it was just me, and I was exhausted.

It all felt like some kind of mad idea I’d woken up with one morning and actually followed through on, even though I no longer had a clue why I’d thought it was a good idea in the first place. There were moments when I found myself standing in the middle of a school playing field with 35 seven-year-olds scattered around its edges, the grass and hedgerows littered with kit and the teachers eyeing me with a look that placed somewhere between gratitude for the chance of a break to serious suspicion.

It was in moments like these that I wondered if there was a point to any of this—if 60 minutes spent shaking some spiders out of a tree would make any kind of lasting impression in the kids’ minds. I, like a lot of people, was feeling exceedingly dubious that minibeasts in pots could really compete for children’s attention alongside everything else in their lives: the rest of their lessons, all the fun at the end of the school year, the promise of summer holidays, social media, TV, friends. In this line up, they could be forgiven for forgetting about an earwig under a log.

Except, they didn’t forget.

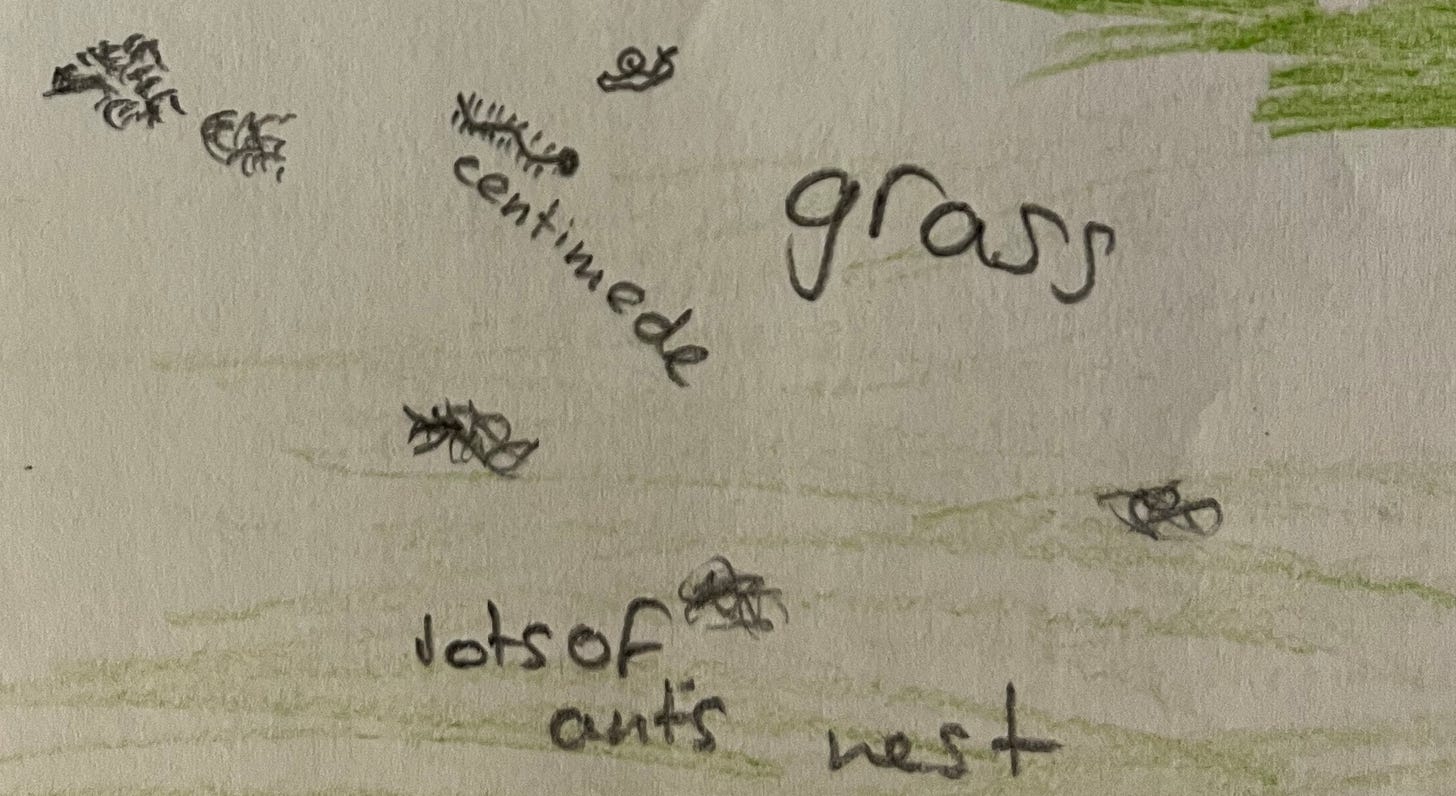

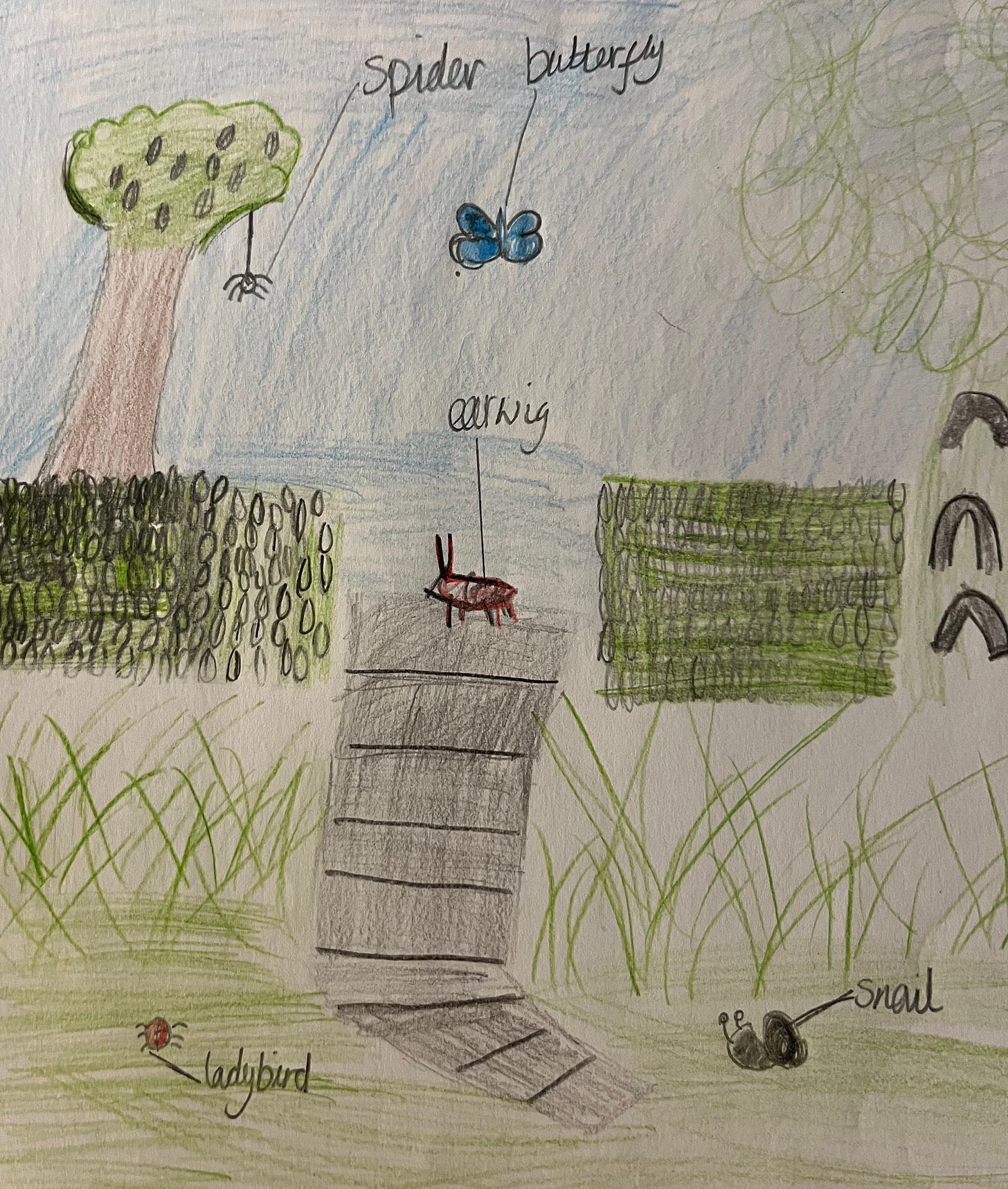

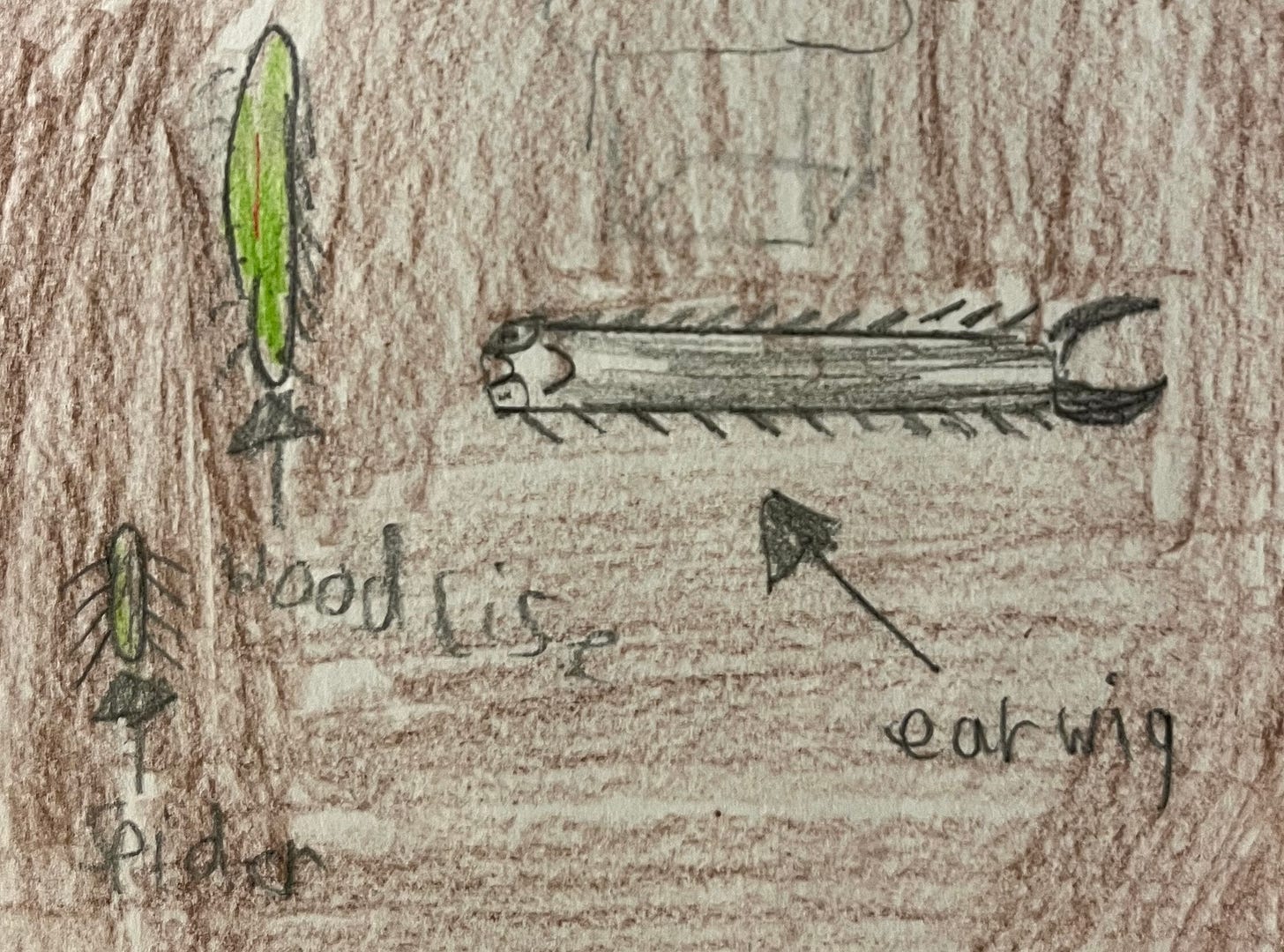

For each class I visited, I got them to draw me their garden or local park three weeks before I arrived. I sent a worksheet to their teachers, with the instruction for them to label all the animals and plants they thought lived in these places. Then, after I visited, I waited three weeks and repeated the same thing.

The drawings I got back were magical.

At one school, we found an earwig. After I had reassured the kids that earwigs do not, in fact, crawl in your ear and eat your brain while you’re asleep, this earwig got passed around in a pot with a magnifying lens in the lid. Although these animals have such a bad reputation, I think in this case it might have worked in their favour. Most of the kids had heard this myth but had never actually seen an earwig, so the opportunity to really look at one, and to centre this experience within a narrative that already existed about earwigs in their minds, even if it were a negative one, meant the kids were especially fascinated to take a proper look.

Three weeks is a long a time for a nine-year-old, especially when the intervening time was filled, as it was, with the school play, sports day and the school’s summer fete. But when I collected those second drawings in three weeks later, over 40% of them contained an earwig. And the details were beautiful.

This earwig story is just one example. In another school, one child managed to catch a wasp, which then got named ‘Wally the Wasp’ and gained quite the reputation. This reputation grew to such an extent that I even received an email a month after my visit from the school’s science lead to say that she was still hearing stories about Wally the Wasp and that the children were still going out to look for him at lunchtime.

A personal favourite outcome of mine was a girl whose first drawing had been of a bare lawn, with the caption ‘I have put my dog Penny because she is an animal’. The dog was the only animal she could think of who lived in this garden. But her second drawing contained a wonderfully detailed drawing of an ant, with all the body segments, legs and antennae!

Now, I have no idea if any of the children remembered the word ‘biodiversity’ or engaged with any of the stuff around sampling strategy or species richness. I didn’t test this. (Now that I’m writing this, I really should have done…)

But the point of these sessions, for me, wasn’t really about teaching them curriculum-style, testable knowledge. It was to see if a single, short session could change their awareness of the wildlife they live amongst and whether or not they felt positively towards it. Sure, I tested this properly through analysing those drawings, plotting graphs and running statistical tests (and yes, the second drawings did contain a greater range of species and more invertebrates than the first drawings.)

But what made those exhausting three months completely worth it for me were the unsolicited emails from grateful teachers, saying just how much the children had retained, and the care taken over those drawings.

I’m not claiming that a single session is enough to change a person’s lifelong attitude to nature. Of course it’s not. But I take a lot of heart in seeing the disproportionately large impression that these single sessions left. If we make the assumption that nature, with its habit of forcing children to slow down and pay attention, can’t possibly compete with fast-paced entertainment, then we’re admitting defeat before we’ve even begun.

Just imagine the impact a weekly session could have, or the effects of outdoor learning built firmly into the curriculum. That’s how we dream big.

So my positive message for you all this week is that Minecraft has nothing on all those squiggly legs of a minibeast.

What’s your experience of the natural world grabbing and holding your attention?

If you find yourself learning something new from this newsletter every week, subscribe for free or upgrade to paid today. It helps keep this work free for others.

Alternatively, you can…

Thank you for your efforts! And - the before and after drawings were a great way of assessing the impact of the experience you provided!

I love this so much!!! You are the superhero of the minibeasts of the future!! And you’ve planted a seed in my garden of hope. I’m wondering what I can do to make a similar experience happen for kids here