When nature fades from memory, it disappears from the world

A story about bees, cultural extinction and the beauty of paying attention

Dear friends,

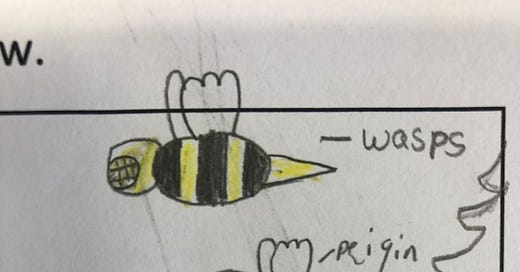

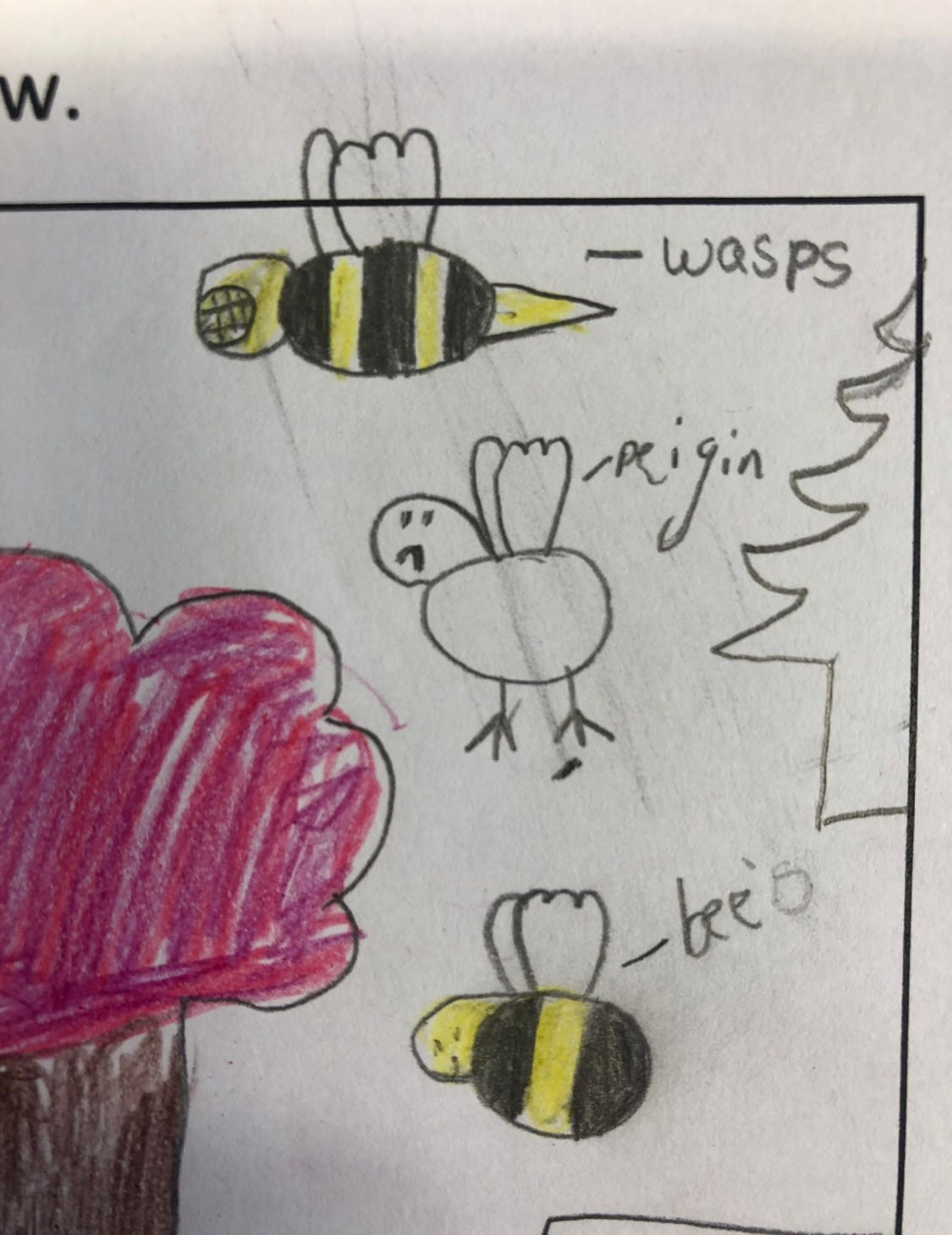

Can you tell the difference between a bee and a wasp? Between a fly and a bee?

I ask this not to shame you but to make you really ask the question of yourself. You don’t have to tell me your answer, but I will tell you mine.

Mostly I can, but I still get caught out quite often, and I have a PhD in zoology for research done in an insect ecology group, of all places. (My supervisor—an actual Professor at the University of Cambridge in entomology—is on this mailing list, so I’m really laying it all on the line for you this week.)

The difference between bees and wasps is actually not so clear cut, which is why I’m keen not to demonise this. Generally, bees are hairier, fluffier and rounder, while wasps are slimmer, smooth and have a tiny ‘wasp waist’. Although, as always in the animal world, there are exceptions.

Flies and bees, however, are more straightforward. Flies have one pair of wings. Bees have two. This is because flies are such speedy fliers that their second pair of wings has evolved into stubby little things called halteres. These help them balance and steer themselves, which to them is more useful than a second pair of wings that just slows them down.

Fine, but being able to tell insects apart won’t save them from extinction though, will it?

Why does this matter?

There was a survey conducted in 2008 in the UK by the National Trust, a heritage and conservation charity, that found 50% of children couldn’t tell the difference between a bee and a wasp. This statistic did the rounds, being quoted in all the newspaper articles about nature and children and what can be done about it all. But I don’t think adults reading these articles truly asked the question of themselves. Because children’s ignorance wouldn’t exist if the adults around them had this knowledge to teach them.

Thankfully, ID exercises that reduce nature to Latin names and tiny differences in antennae don’t matter, so while this is sad and poignant—decades ago, this knowledge would have been commonplace—the world has changed, and we must accept it.

Except, this really does matter.

Again, this is not to shame or blame you. I have held my hands up too. But we must do the work to understand why we should care about this lost knowledge before we can muster sufficient motivation to build it back.

The answer to why this matters lies in social science, not entomology.

Bear with me while I do a deep dive into a social science paper. I have read it so you don’t have to.

The concept that matters here is societal salience. It’s a mouthful, but it captures something so important and understandable. What it means is how aware a society is of something—of a particular species, say.

This is significant because there are several ways in which an animal or a plant can go extinct. One is the standard way: biological extinction, when there are no more individuals left in the world. Then, there’s functional extinction, when there is a small population left, but there are too few individuals for them to perform their usual role in the ecosystem (e.g., too few mussels in a river for water purification). The third, less tangible way, is societal extinction. This is when a species no longer exists in our collective cultural memory—no more mentions of it in art, literature, music.

The problem is that a species often peaks in societal salience—i.e., we become most aware of it—right before it suffers biological extinction. Usually, this is because it becomes so rare as it nears extinction that it attracts plenty of attention as conservation charities scramble to save it.

A good example of this is the northern white rhino. This is a subspecies of rhino whose last male died in 2018, leaving just two females in all the world. For most people, the first they heard of this species was most likely in 2018 when the news broke that last male had died, or maybe just before this in 2009, when the four last remaining northern white rhinos in the world were moved to a conservancy in Kenya, to be protected by round-the-clock armed guards.

The point here is that this subspecies has become most famous and prominent right at the moment when it is staring straight down the barrel of extinction. This is not unusual. This increase in attention often happens too slowly or too late to translate into effective conservation action, so a species can peak in its cultural prominence immediately before becoming biologically extinct.

If today’s children enjoy only minimal interaction with the natural world, nature will not feature in the culture they produce—in their art, music, literature, poetry. A recent study by the psychologists Selin Kesebir and Pelin Kesebir found exactly this. They looked at fiction, song lyrics and film storylines across the 20th century and into the 2010s. They asked how references to nature had changed over this time period. Across all three types of cultural product, they found that references to nature have been in steady decline, while references to the human-made environment have not.

If we continue along current trends, whole hosts of species will be disappeared from cultural memory in a generation, and we will not even have the capability of noticing when they are disappeared from the world.

It’s so easy to shrug and turn away from the field guide because who needs Latin names anyway. But the point here is that it’s not really the field guides and Latin names that matter.

What matters is showing ourselves and our children the joy that these species can bring to our lives and to the world.

Through this, we end up paying attention to their beautiful details—to the tiny, fluffy hairs on the legs of a bee, to the delicate, complex moving parts of the face of a stick insect—because we feel emotionally connected to them.

Whether or not we are motivated to then learn the Latin name for the animal in front of us is neither here nor there; some of us will, and they will go on to be the entomology professors, but some of us won’t, and we will go on to write about them, draw them, love them and care for them. (Not that entomologists don’t also care about them, but you get my point.)

Our attention matters because we will then be able to notice if they are in trouble, ideally before things get as bad as they have with the northern white rhino.

That’s why encouraging children’s natural joy at tiny creatures is so powerful. It rekindles our own, and this joy is contagious amongst adults.

In fact, I stopped writing this post part way through to revive a drowsy, hungry bee that had bumbled its way into our soap dish. Reviving it with sugar water and helping it outside onto a flower brought me joy. It made me stop and look at it in detail. Awe isn’t only inspired by big things. It’s also conjured by the very small things that make us bend over to look at them.

This week, I’m leaving you with not just a good, solid, academic-backed reason to rekindle and cherish your joy over the small things, but also permission to know that this is one of the most powerful and important things you can do. Go forth!

I’m so intrigued, and I shall not judge you—can you tell the difference between a bee and a wasp?

Upgrade to paid today or subscribe for free to help fix our broken relationship with nature.

Alternatively, you can…

I’m a teacher in Slovenia and I’m happy to tell you school here is still mostly about being in nature. As adults it does change and whilst people spend time outside it’s more to climb a mountain at speed than to look at the flowers and insects. It’s taken for granted but the children’s songs and books are mostly focused on nature compared to my native England!

I love this! Identification is about meaning. Years ago I worked as a science teacher with a media arts teacher. We showed a group of 9th graders photos of tree leaves from campus. They’d seen these trees every day (spring-fall) they came to school (for some of them this was 11

years). They could identify less than half of the trees in the photos. Then we showed them images of advertising icons such as Apple, McDonalds, Levi’s, etc. They knew all of them. People value what they are taught to identify and value, not what is intrinsically valuable. Bees, wasps, and flies are all essential pollinators (and wasps are great pest control). This needs to be taught.