Research Deep Dive: What children’s drawings reveal about biodiversity bias

Exploring the hidden conservation consequences of childhood perceptions of rainforests

Dear friends,

Welcome to the first Research Deep Dive—exclusive monthly posts for my paid subscribers. Each month, I delve into the nitty gritty of a research paper on nature connection, or on the health and wellbeing benefits of biodiversity.

I’m starting this series because there’s a lot of fantastic research out there on our complicated relationship with the natural world, and this body of literature is growing rapidly. This type of research—at the interface of social science, ecology and conservation—is vital to understand if we are to make progress on halting climate change and biodiversity loss. But this angle—how people feel, think and learn about nature—is often forgotten.

I’m putting the Research Deep Dives series behind a paywall because these posts take longer, and more expertise, to write than my more musing Friday posts. If you are intrigued by the fine detail and want the deep dive, upgrade to paid today.

I have so many cool papers that I can’t wait to tell you about! So, let’s get into our first one.

‘Children’s Perceptions of Rainforest Biodiversity: Which Animals Have the Lion’s Share of Environmental Awareness?’

I love this paper (and that title). It analyses kids’ drawings to get a better grasp of their perceptions of a rainforest.

Why? Because public perceptions of rainforests, and of the natural world in general, are often quite different from the complex ecological reality of what ecological systems comprise and how they function.

This matters because public perceptions and values are crucial factors in determining media interest, science research and funding, and by extension the focus of conservation efforts. If these efforts are more often targeted towards large, charismatic animals (like pandas), but consistently sideline smaller, ‘less interesting’ invertebrates and plants, there are knock-on effects on the effectiveness of conservation.

What did the researchers do?

Three researchers at the University of Cambridge (Full disclosure: one of whom supervised my PhD, but I write this as objectively as possible) asked 167 children to draw a picture of their ideal rainforest. The children were between the ages of 3 and 11 years old, and they were persuaded to do this because it framed as a competition, which presumably meant the kids took it seriously and thought properly about their drawings.

The researchers then looked at the drawings and counted the number of times each child had drawn certain types of animals.

The animal categories were:

Mammals

Birds

Reptiles

Amphibians

Fish

Insects

Social insects (ants, termites, some bees and some wasps)

Spiders

Annelids (segmented worms, like earthworms)

Molluscs (snails and slugs)

Centipedes

To see if there were biases in the children’s perceptions, these data were then compared to information on the actual composition of a rainforest.

To do this, researchers found an estimate for the total biomass—the total weight of all the individual animals in a particular group—for each of the animal categories for a central Amazonian rainforest. This is a really important metric because it gives us an idea of the relative contribution to the functioning of an ecosystem made by a particular group of animals.

They also looked at the total number of species in each of the animal categories, which tells us about the diversity of each of these groups. For example, insects are much more diverse—i.e., there are many more insect species—than mammals. This matters because each species will have a slightly different effect on an ecosystem due to the way it lives—how it moves nutrients through the system, how it behaves and what it eats, for example.

What did they find?

The results were really clear. There is a serious skew in the children’s perceptions of a rainforest. What they think a rainforest is made up of is significantly different from how it is made up in reality.

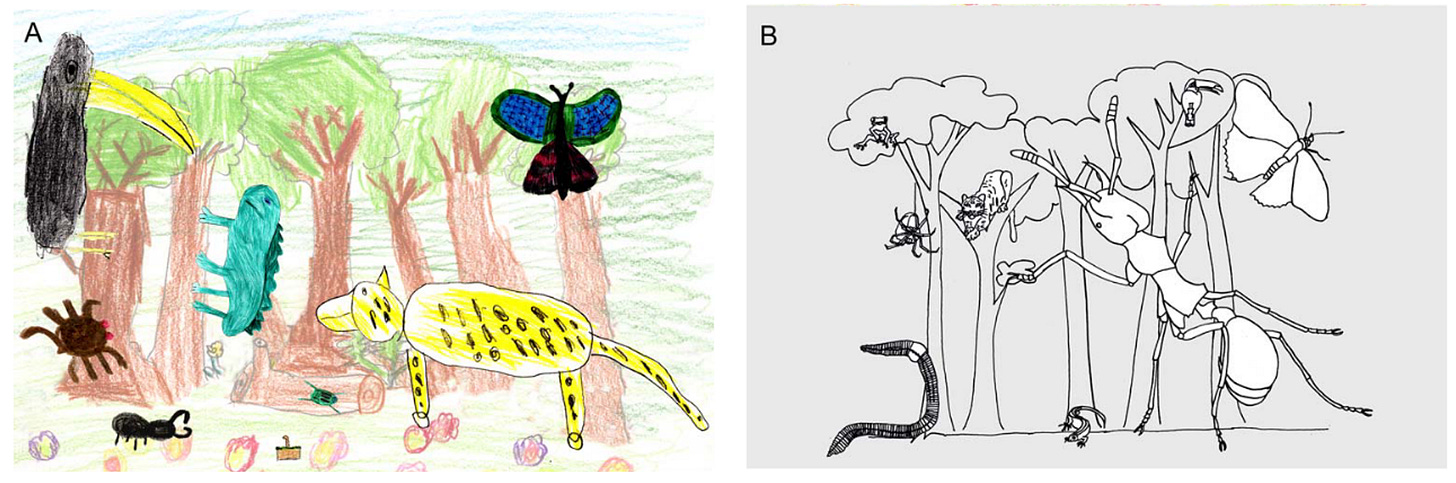

The figure below is an ingenious way of representing their results. The researchers used parts of the children’s drawings to create a ‘species scape’, in which the size of each of the elements is in proportion to the frequency at which it was drawn. They’ve then done the same thing with line drawings to represent the actual make-up of a central Amazonian rainforest. Looking at these, it’s instantly obvious what the problem is!

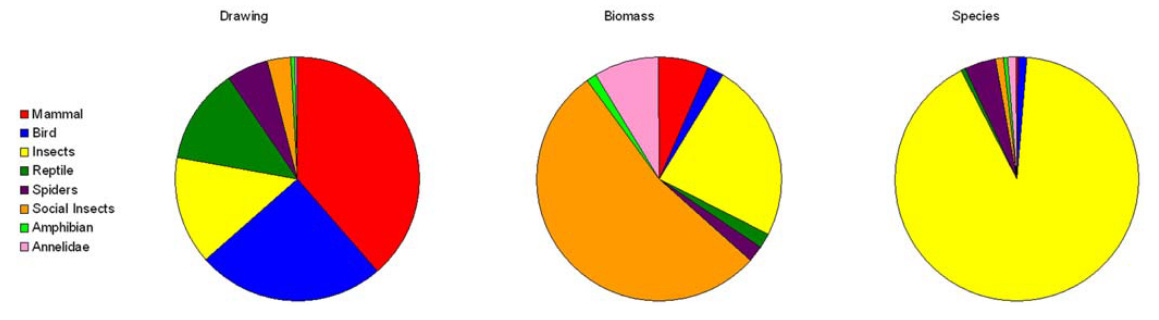

As compared with the biomass of an actual rainforest, children massively over-represented the importance of mammals, birds and reptiles, while under-representing the importance of social insects and annelids (those segmented worms). The same is true when looking at the number of species. Again, mammals, birds, reptiles and fish were over-represented, while insects were under-represented.

In plain speak, this means that children here in the UK think that a rainforest is mainly made up of vertebrates (animals with a backbone, like us), in terms of weight and number of species. In reality, most of the animal biomass and diversity of animal species in a rainforest in made up of invertebrates (animals with no backbone, like insects, annelid worms, molluscs and spiders).

Just look at these pie charts! The one on the left shows the composition of the children’s drawings, with the different colours representing the different animal categories. The one in the middle uses the same colours to show the biomass—total weight—of each of the animal categories in a central Amazonian rainforest. The pie chart on the right shows the number of species in each category.

The difference in colours really drives these results home, doesn’t it?

You can see instantly the massive over-representation of the red category (mammals) in the drawings versus reality, and the huge under-representation of the yellow category (insects).

Why do we care?

We care because the same biases we see in the children’s drawings are reflected in conservation research, action and funding. Current targets for biodiversity conservation, and the ways in which we monitor biodiversity loss, similarly overlook invertebrates, despite them representing the majority of animal biodiversity. This means that we are consistently failing to prioritise research into the ecology of these species, even though they are vital for our functioning biosphere and the health of the planet.

And because we know less about invertebrates than vertebrates, they tend to feature less in our lives—in media, as pets, out and about in the world. (How many times do we brush ants off our legs when we’re having a picnic instead of watching them scuttle or gently picking them up?) Thus we perpetuate a cycle of being less familiar, appreciative and curious, and more fearful, neglectful and even destructive, towards the most important animals in an ecosystem.

This has worrying implications for how we go about protecting natural environments, so it’s important we try to redress these biases in how we think about and look at nature.

How cool is this research?! I love how they’ve used children’s drawings to access their perceptions about the natural world, rather than getting them to complete some kind of survey. This is meeting them where they’re at, so the results are much more likely to be an accurate representation of what the children actually think.

Full credit to the three authors of this paper: Jake Snaddon, Edgar Turner and William Foster. If you would like to read the full paper, click here.

I hope you’ve enjoyed the first of my Research Deep Dives series and that it has left you with some food for thought. I’ve really enjoyed writing it, and I am already looking forward to writing the next one!

Let me know your thoughts in the comments, both on the research itself and on this post. I want to know how I can make this series the most useful for you.

If you want to learn more about research on nature connection, subscribe for free or upgrade to paid today.

Alternatively, you can…